Aegean Layout

The layout for the Aegean Quick Start book wasn’t created using InDesign or Scribus or any standard design tools. I don’t have any experience with either so I found them difficult to get started with. I do have a background in programming, web development and UX, so I made use of the skills and tools I already had.

I had a number of goals for the book. I wanted to have both a PDF and a short (possibly one-off) print run and with printing costs I knew it was going to be black and white interior with a colour cover and around 100 pages in length. I was originally thinking around 60 pages, but Inky Little Fingers are amazing and increasing the page count to 100 B&W didn’t have that big an impact on the price.

I had a number of goals for the book. I wanted to have both a PDF and a short (possibly one-off) print run and with printing costs I knew it was going to be black and white interior with a colour cover and around 100 pages in length. I was originally thinking around 60 pages, but Inky Little Fingers are amazing and increasing the page count to 100 B&W didn’t have that big an impact on the price.

Design

Despite planning a print-run, my main focus was for a digital product, so most of the design decisions revolved around that. My first decision was to have a single column of text. A double column of text is great for a physical book but on a screen I find I can’t fit the whole height of the page at a comfortable reading size. Which means I’m constantly scrolling down a little to read the end of a column then up again to read the top of the next column. There are no shortcut keys available for that and it hinders my attention.

That first choice informed a lot of the remaining decisions and, eventually, had a big impact on the writing. It meant the book had to be small scale as a line length beyond around 50em (60–70-ish characters) is hard to follow. I’m also so over massive weighty RPG tomes (but that’s another article) and a huge fan of Blades in the Dark and its ilk. I love the smaller scale books that Evil Hat produces and I wanted something of a similar scale. In Europe, that would be A5 rather than the 6” by 9” that Evil Hat uses.

That first choice informed a lot of the remaining decisions and, eventually, had a big impact on the writing. It meant the book had to be small scale as a line length beyond around 50em (60–70-ish characters) is hard to follow. I’m also so over massive weighty RPG tomes (but that’s another article) and a huge fan of Blades in the Dark and its ilk. I love the smaller scale books that Evil Hat produces and I wanted something of a similar scale. In Europe, that would be A5 rather than the 6” by 9” that Evil Hat uses.

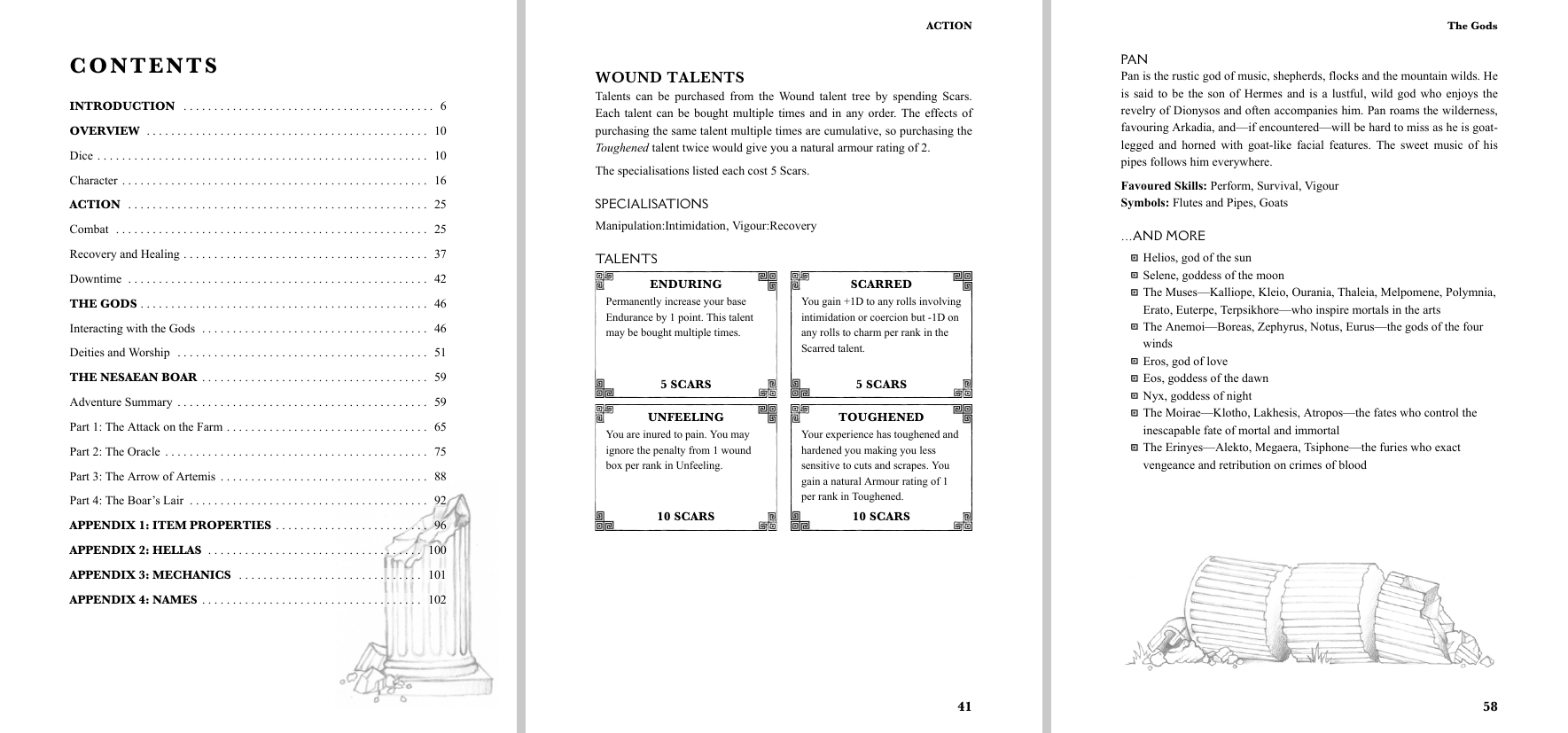

The digital version had to be easy to navigate. Chapter headings must be bookmarks so the PDF viewer can display them. The table of contents must be a clickable (or tappable) link to the relevant section. These seem like minimum requirements but I have a number of RPGs in PDF format from large, well-known companies which don’t have this. It makes the PDF frustrating to use and means, if I’ve only bought a PDF of your game, I probably won’t play it.

Following on from this, if the text mentions a page number for more information, e.g. Resolve (pg. 21), that text should look different and link to the correct section in the digital version. It doesn’t need to look different in the print copy, just having the page number in place is enough. The page number in the corner of the page must match the page number the PDF viewer is on. If I use a shortcut key to go to page 15 of the PDF that should be page 15 of the book which (obviously) should be the same as page 15 in the print version.

There are some other small stylistic differences between the print and digital version of the book. The print version has page numbers in the bottom outer corners of the book spread and has the name of the game in the top left and the chapter title in the top right. So the facing pages have a different header and footer, just like in 90% of every book ever printed. On a screen there’s no real concept of a page spread, just a continuous page scroll (though your PDF viewing software can probably display as a spread if you want). In the digital version the page numbers always appear in the bottom right corner and the top right corner always has the chapter name.

There are some other small stylistic differences between the print and digital version of the book. The print version has page numbers in the bottom outer corners of the book spread and has the name of the game in the top left and the chapter title in the top right. So the facing pages have a different header and footer, just like in 90% of every book ever printed. On a screen there’s no real concept of a page spread, just a continuous page scroll (though your PDF viewing software can probably display as a spread if you want). In the digital version the page numbers always appear in the bottom right corner and the top right corner always has the chapter name.

Technology

So the digital and print versions are different, with some additional constraints specified by the printers. Managing two different versions of a book quickly becomes a writing and editing nightmare, especially for a team of one. So how is this handled? By writing everything in Markdown and having a build process to generate the print and digital version of the PDF, along with an EPUB version.

Markdown is a simple syntax for formatting text. It allows for simple lists, headings, quoted text and the like, and is easy to convert to HTML. You can also embed HTML directly into the page which makes it quite flexible. Once converted to HTML you can use CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) to manage the look of the page. HTML and CSS are the backbone of the web and are used to display every website you’ve ever visited. They’re also used to format EPUB books, so converting everything to HTML is a great first step.

Once everything is in HTML and CSS I use Prince XML to convert to PDF. Prince supports all of the CSS 3 page layout functionality (with some extensions) so can generate page numbering, internal links within the PDF, and manage the headers and footers of each page. It’s not cheap and there are free alternatives out there now but when I was creating the book nothing came close to Prince’s functionality.

The build process is created using Metalsmith which is a pluggable file processor. At its most basic all it does is copy files from one directory to another but it gives you methods for manipulating the files as they’re copied. It supports YAML headers in the Markdown files so you can store data along with text. For example, this is the YAML header for the introduction chapter:

---

title: Introduction

collection:

- chapters

- quickstart

sort: 0

---

There’s a lot of potential here, which I’ll dive deeper into in another article, but I’ve set up rules which warn me if anything is missing a title and I can reference things by their collection rather than repeating the content. Beyond this, the main thing Metalsmith does is convert everything to HTML then run Prince and the EPUB generator over the output. This results in a print PDF, a digital PDF, the print cover, and the EPUB version being created all at once from the same source content.

Pros and Cons

The main pro to all of this is there’s no repetition of content. If I fix a typo it’s fixed in all three versions of the book and it’s built at the touch of a button (well, Command+B) in about 3–4 seconds. I also briefly touched on referencing, which has an impact on rules consistency. For example, if I change the damage of a weapon, I only need to change that in one place and everything else, including adversaries using that weapon, automatically pick up the change.

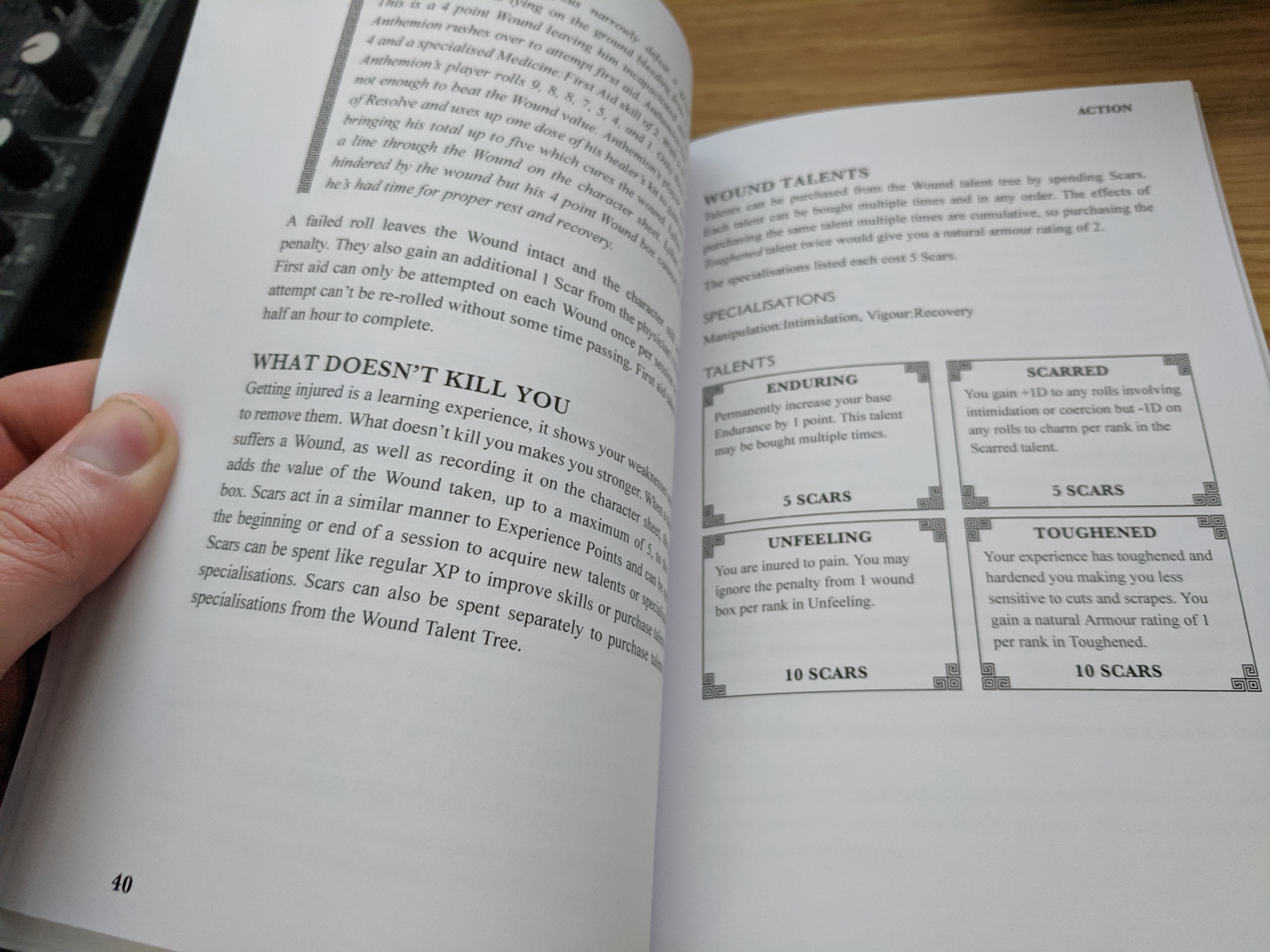

The main con is it’s not a visual process. It’s fine when you’re setting up your basic layout as I can picture that fairly easy — I use this stuff daily so it’s become second nature. Eventually with an RPG book you end up editing for layout and that’s where it becomes difficult. You can easily see in the PDF that you need to remove 20-ish words from a section to remove an orphan word creeping onto another page but you can’t see that when you edit. You have to edit then build again to see the result. So what would be a seamless editing process with Scribus becomes a slightly disconnected iterative process.

I do have rules in place to prevent this — orphans and widows are both set to 2, so Prince will never allow 2 words at the end of a line or 2 lines to go onto the next page and having a single column helps — but these things frequently need human judgement so can’t (currently) be fully automated.

Overall I would say it’s worth it. Editing for layout took longer than it should have but the amount of time saved in other areas is immense. I’d probably still be formatting the print version and struggling to fix typos across multiple editions if I’d gone with a manual process.